Mind the Gap

Highlighting MENA’s

Climate Finance Challenge

Introduction

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region is highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. While most countries in the region have committed to implementing adaptation and mitigation measures to combat its effects, these plans remain largely uncosted. Those countries that have specified funding requirements have received far less than what is needed. Access to financing varies across the region; however, overall, MENA remains significantly underfunded and is therefore underprepared for the climate crisis.

“Mind the Gap: Highlighting MENA's Climate Finance Challenge” examines the current state of climate financing flows into the region from global climate funds. Its authors collected, collated, and analysed data from public domains on more than 350 projects from the big three climate funds: the Green Climate Fund (GCF), the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and the Climate Investment Funds (CIF), as well as their sub-funds. Using this data, the report identifies key drivers, challenges and positive indicators impacting MENA countries' efforts to attract climate financing. The data analysis contained in the Appendix to this report underpins the key findings and should be drawn upon as a resource for others examining this critical issue.

19 MENA countries were considered for this study: Jordan, Lebanon, Iraq, Syria, Palestine, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Qatar, Oman, Kuwait, Bahrain, Yemen, Egypt, Tunisia, Morocco, Algeria, Libya, Sudan and Djibouti. A major limitation in assessing environment and climate finance is that the data listed in the public domain for most projects is inclusive of financing covering all participating countries in any one project. Thus, the exact breakdown per country is not always available, and available data on official websites is not always updated regularly. Therefore, greater transparency on climate finance is needed. For the purpose of this study, the data has been adjusted to an estimate reflecting funding per country, per project.

Executive Summary

- The MENA region's climate financing from the big three global climate funds and their sub-funds equates to only 6.6% of total global climate financing, as of November 2023. Including mobilised co-finance, the region's total climate finance to date is $24.4 billion - among the lowest shares globally.

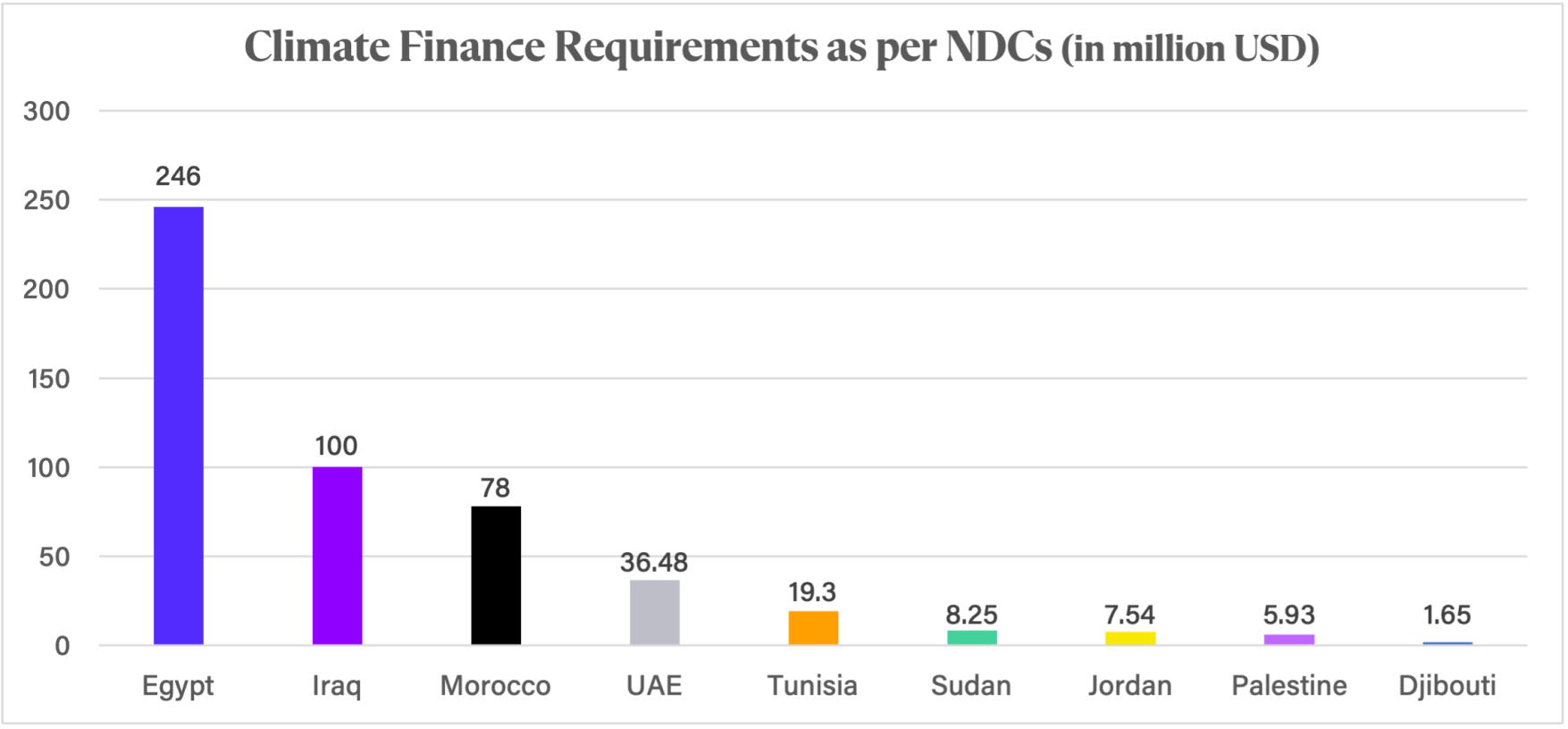

- Climate funding to the MENA region needs to be increased by a factor of 20, at least, to reach the overall financial requirement of the nine countries (Egypt, Tunisia, Morocco, Jordan, UAE, Iraq, Djibouti, Palestine, and Sudan) that have quantified their climate costs in their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). This requirement, as stipulated in the NDCs, is $495 billion. Just two countries - Egypt and Iraq - account for 67% of the total.

- The bulk of the financing approved for MENA from the big three global climate funds is heavily centralised in a few countries. Approximately 78% of approved funding (excluding co-financing) has been earmarked for North African countries; Morocco and Egypt account for more than 60% of the total. More than half of the approved funding is loans, adding pressure to overall debt issues.

- Countries in receipt of the highest levels of financing are those that have tapped into several funds. The region's frontrunners, Morocco, Egypt, Tunisia and Jordan (see Figure 4), which account for 86% of the total approved climate funding, have accessed all three of the major global climate funds. The three North African countries are also able to access funds that are solely focused on Africa, as well as funds with broader geographical remits. Conversely, those countries with much lower levels of financing, such as Yemen, Iraq, Syria, Libya and four Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, have only tapped into funding from the GEF, whose disbursements are much lower in value than the other major funds.

- Energy-related projects receive the highest proportion of climate finance in the MENA region. The CTF, a clean energy technologies sub-fund of the CIF, is among the largest climate funders in the region. The GCF has allocated 58% of its approved funding in MENA to energy projects. Energy projects have also enabled funding inflows into specific countries that have prioritised renewable energy deployment such as Morocco and Egypt.

- Countries with a proven track record in applying for, receiving, and implementing project financing from international climate funds, such as Morocco and Egypt, have been shown to be more successful in accessing subsequent funding. They can demonstrate in their applications adequate capability to attract co-financing. Thus, they have an enhanced capacity to develop investment plans, draft funding proposals, engage with the various agencies, and deliver on the expected key performance indicators.

- Countries applying for climate finance are challenged by complex application procedures, which often require financial or technical assistance to complete. Furthermore, the long application and approvals process - averaging 4-5 years at the GEF and GCF - is not conducive to managing the risks and costs involved in projects, which change over time. This limits the efficacy and impact of the funding and of associated projects.

- The need to establish and demonstrate a proven track record is preventing some of the region's most at-risk countries from making progress on adaptation and mitigation measures. Lack of technical and often financial capacity, as well as political stability, is a key challenge. Fragile, or conflict-affected states, such as Iraq, Yemen and Syria, find it difficult to meet the eligibility criteria for international financing from climate funds due to the low prioritisation of climate action, little to no institutional capacity, slow engagement with the UNFCCC and its related processes, difficulties in collecting climate-related data, and deteriorating or unsafe security environments.

Climate Change in MENA

The MENA region, already the most water-scarce globally, is extremely vulnerable to climate change. More frequent irregular weather patterns, extreme temperatures, drought, and recurrent flash floods are being recorded, particularly in the Gulf, and sandstorms are becoming more intense, especially in Iraq.

Climate change is a threat to food, water, and energy security of MENA countries and has the potential to exacerbate existing socio-economic challenges in the region, as well as to create new ones. It negatively affects agricultural yield productivity and increases demand for cooling and desalinated water and is a threat multiplier for political instability, migration, and displacement.

The expected economic cost of dealing with the effects of climate change ranges from 0.4% to 1.3% of GDP in MENA countries and could reach 14% if mitigation and adaptation measures are not adequately implemented.1 Mitigation measures are those implemented to reduce the severity of the impacts of climate change, by preventing or scaling down greenhouse gas emissions. Adaptation measures are those implemented in anticipation of the adverse effects of climate change. In other words, they involve adjusting - technologically and behaviourally - to the current and expected impacts of climate change.

To address climate risks, most MENA countries have committed to implementing mitigation and adaptation measures and have submitted to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). An NDC is the climate action plan required of parties signed up to the Paris Agreement. It outlines a country’s approach to, and targets for, cutting emissions and adapting to the effects of climate change. Countries such as Egypt and Morocco have also launched national strategies for addressing climate change; others, including the GCC countries, Jordan and Egypt have initiated national climate adaptation plans; and Saudi Arabia has established a climate action umbrella, the Saudi Green Initiative, and leads its regional equivalent, the Middle East Green Initiative. National climate committees have been established in several countries, including Oman, Qatar and Kuwait. Except for Qatar, all GCC countries have pledged to reach net-zero emissions by 2050 or 2060. Saudi Arabia’s net-zero commitment also includes a 30% reduction in methane emissions by 2030.

A Drop in the Ocean: MENA's Share of Global Climate Financing

A major limitation in assessing environment and climate finance is that the data listed in the public domain for most projects is inclusive of financing covering all participating countries. Thus, the exact breakdown per country is not always available. When available, the data on official websites is not always updated regularly and could be as much as a few years old. For the purpose of this study, the data has been adjusted to an estimate reflecting funding per country, per project. The estimate was reached by splitting multi-country project funds between participating countries while accounting for funding allocated to a specific country. The inability to obtain exact figures demonstrates that more transparency on climate finance is needed.

A total of 19 MENA countries were considered for this study: Jordan, Lebanon, Iraq, Syria, Palestine, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates (UAE), Qatar, Oman, Kuwait, Bahrain, Yemen, Egypt, Tunisia, Morocco, Algeria, Libya, Sudan, Djibouti.

The UNFCCC defines climate finance as “local, national, or transnational financing - drawn from public, private and alternative sources of financing - that seeks to support mitigation and adaptation actions that will address climate change.”2

Despite its vulnerability to climate risks, the MENA region has limited access to climate and environment-related finance compared to other global regions such as East Asia and the Pacific Islands. According to the UNFCCC Funds and the Climate Funds Explorer database, MENA countries are eligible for financing from 24 international climate and environment-related funds.3 The largest of these are the Climate Investment Funds (CIF), and the UNFCCC's own financing mechanisms: the Global Environment Facility (GEF), and the Green Climate Fund (GCF), which are the world's largest funds.

These three funds, along with most of their sub-funds have been assessed in this study. This includes all the sub-funds of the GEF in the public domain and the Clean Technology Fund (CTF), which disburses the bulk of the CIF's funding to MENA. An analysis of each fund and sub-fund is included in the Appendix of this report.

Between 1992 and November 2023, of the total amount of climate and environment financing made available by the big three climate funds and their sub-funds, approximately $2.7 billion was approved for projects in MENA countries - equivalent to just 6.6% of global financing. In addition, the region saw inflows of $21.7 billion in co-financing from bilateral and multilateral development banks, governments, and private sector. Thus, the cumulative climate financing for the MENA region exceeded $24.4 billion in this period; however, its share of climate finance remains one of the smallest globally. It is difficult to account for MENA's low share of global climate financing. ESCWA suggests that it could be due to the complex processes involved in applying for funding,4 which does not provide a full explanation and requires further investigation.

Figure 1 compares MENA to the world in terms of the amount of approved financing, number of projects, and countries covered for the funds, as well as the share of loans in total financing, the share of multi-country projects, and the total value of approved projects involving one or more MENA country.

| Climate Funds | Share of MENA versus Globally | ||

| Projects | Approved Funding (S) | Countries Covered | |

| Green Climate Fund | 24 out of 119 | $967 million out of $12.7 billion | Countries out of 148 and readiness programmes in 5 additional countries and country presence in additional 2 |

| 68% share of total funding in form of loans | |||

| 62% are multi-country projects | |||

| Total value of approved projects involving 1 or more MENA country = $2.5 billion | |||

| 315 out of 5,000 | $858 million out of 23 billion | 17 out of 186 | |

| Global Environment Facility | Bulk of funding is in form of grants | ||

| 24% are multi-country projects | |||

| Total value of approved projects involving 1 or more MENA country = $1 billion | |||

| Clean Technology Fund (a sub-fund of the Climate Investment Funds) | 13 out of 161 | $857 million out of $5.3 billion | 4 out of 34 and investment plans prepared in additional 2 |

| Bulk of funding in form of loans | |||

| Projects are national, country-focused | |||

Additionally, the bulk of the global climate funds' approved financing for MENA is heavily centralised in just a few countries. Approximately 78% of the $2.7 billion in financing has been earmarked for North African countries. More than half of this is in the form of loans, adding pressure to MENA's overall debt issues. In fact, public debt levels of countries within the region are particularly high. For example, in Egypt the debt-to-GDP ratio has crossed 92.9%; in Tunisia, 80%. Interest rates are also rising, making the cost of servicing the debt far greater.5

MENA's largest source of climate funding is the GCF. It has approved $967 million in total for the region in addition to co-financing estimated at $3 billion. This exceeds the cumulative project financing of the two other funds, CIF and GEF: $1.7 billion. There are wide discrepancies in the amount of co-finance mobilised by the CIF and GEF. The CIF has leveraged the largest amount at $12.6 billion, a 15-fold increase over the $860 million it has approved in financing. In contrast, the GEF, which has a 1:7 co-financing ratio, has approved roughly $6.1 billion in climate financing and co-financing in total.

Factoring in co-financing, this brings the total climate financing approved for the MENA region from the big three funds to $24.4 billion.

The bulk of MENA’s total approved climate financing was made available in the past decade. When accounting only for funding approved from 2010 to 2023, the cumulative financing from these funds drops by 18% to $2.2 billion, and the co-financing becomes $19 billion. This is mostly because the GCF and CIF funds approved projects in MENA within this timeframe, whereas 45% of the GEF funds approved projects between 1992, in the GEF’s pilot phase, and 2012 during its fourth replenishment cycle, GEF-4.

Under Pressure and Under Funded

Without adequate financing, MENA countries will be unable to implement the mitigation and adaptation measures needed to weather the impact of climate change. The socio-economic, environmental, and political challenges of the region will increase as a result.

Even though the region's total climate financing from the major funds has reached $24.4 billion, funding needs to be increase by a factor of 20, at least, to reach the NDC goals of the nine MENA countries that have quantified their financial needs in their NDCs and national climate plans by 2030-40. The climate finance requirements of these nine MENA countries, which are Egypt, Tunisia, Morocco, Jordan, UAE, Iraq, Djibouti, Palestine and Sudan, is estimated at $495 billion in total. Just two countries, Egypt and Iraq, require approximately 67% of this amount. The overall costed climate finance needs will drastically increase when the ten remaining countries announce their costed needs as stipulated in their NDCs. Figure 3 shows the total climate finance requirements of the nine MENA countries that have costed the needs of their NDCs to date.

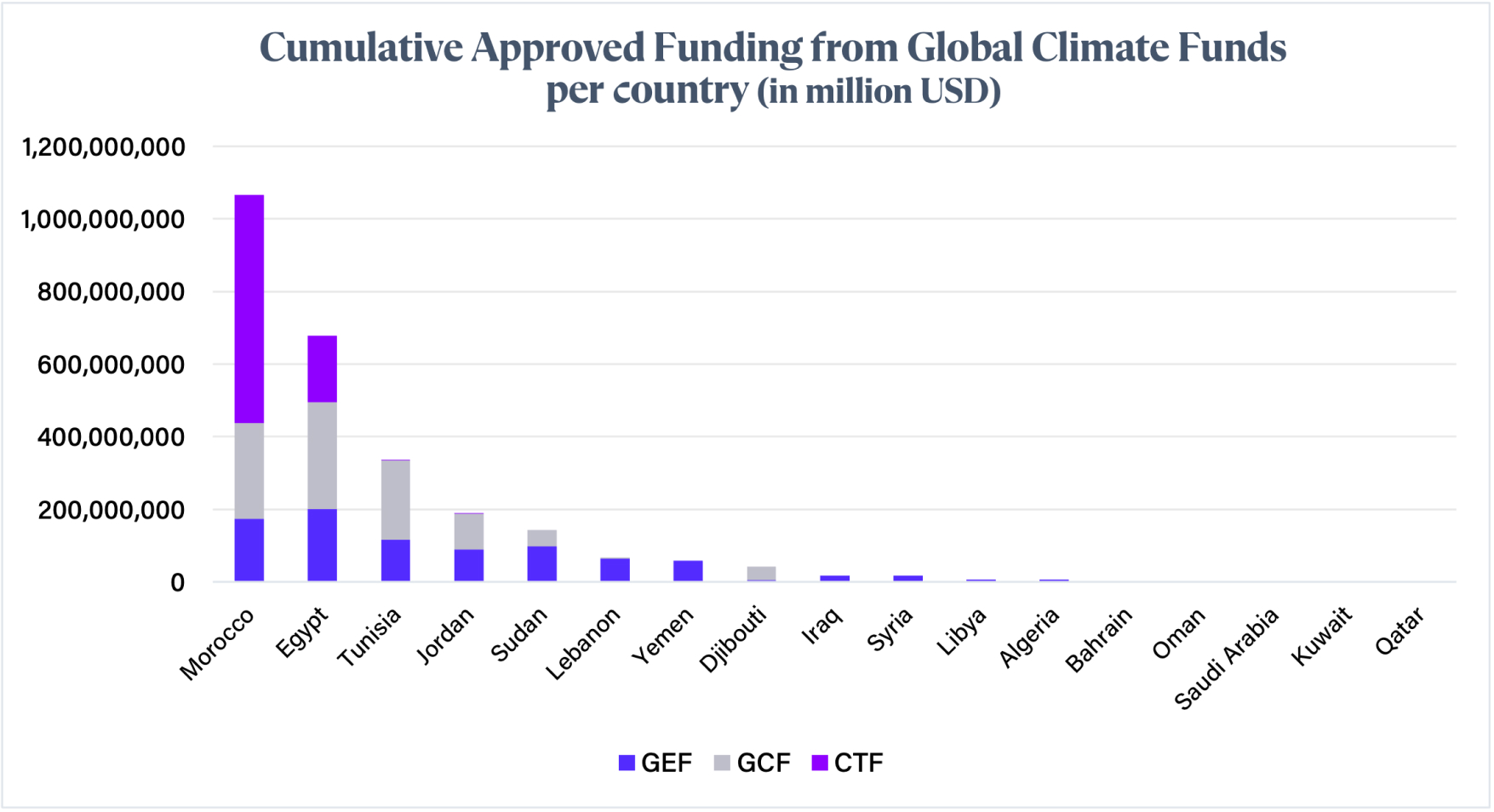

The data suggests that there are wide discrepancies in the allocation of funding across MENA countries. Morocco and Egypt account for 66% of the cumulative MENA approved funding from the big three global climate funds. The total funding approved per MENA country from the GEF, GCF and CTF is listed in Figure 4.

Money Attracts Money and Capacity Equals Cash

Of the countries that have applied for financing, those that have been successful in securing both climate financing and high levels of co-financing have the capacity to secure additional resources for climate-related initiatives and projects. Some countries, particularly in the GCC, have only applied for small amounts of funding, mostly for the preparation of climate and biodiversity-related reports and communications (see Appendix sub-section 3).

The highest share of projects is only partially funded by global climate funds. Thus, most applications must demonstrate a strong ability to attract co-financing. The GCF fund has a co-financing requirement whereas the GEF mandates co-financing only for projects that are classified as full- and medium-size.6 However, GEF financing is intended to complement national programmes and policies and is provided for incremental costs rather than the full cost of projects.7 It also aspires to reach a co-financing ratio of 1:7, thus, project proposals need to demonstrate co-financing capacity of at least $6.00 for every dollar the GEF contributes. This co-financing ratio has been achieved in the case of the cumulative GEF financing for MENA.

The four countries leading the region in approved climate finance - Morocco, Egypt, Tunisia and Jordan (see Figure 4) - together hold more than $2.2 billion, or 86% of the total approved climate funding, and have accessed all three of the major global climate funds. Conversely, those countries with much lower levels of financing, such as Yemen, Iraq, Syria, Libya and four GCC countries, have only tapped into funding from the GEF, whose disbursements are much lower in value. Among the GCC countries, Bahrain holds the largest portion of climate finance. It has drawn from both the GEF and the GCF; however, the bulk of this is for technical assistance on projects, and so is low in value.

Additionally, the data demonstrate that the countries within the MENA region in receipt of the highest levels of financing are those that can tap into several funds and participate in projects that cross different regional categories. Egypt is a prime example. As part of Africa, Egypt can draw upon financing from geographically specific funds, such as the Canada-African Development Bank Climate Fund (CACF), as well as from funds with a broader or unspecified geographical scope. Multi-country projects have also opened up significantly more resources in funds such as the GCF. In total, Egypt has accessed approximately $678 million for climate and biodiversity projects from the big three global climate funds. In addition to the funds it has already accessed, in 2022 Egypt was selected as one of the first participants in the CIF’s Natures, People and Climate investment programme.

In general, Egypt has been more successful than many of its regional peers in attracting climate finance and foreign investments, even though it has not yet set a net-zero target and its investment environment is considered problematic due to fiscal challenges and economic instability. The country has devised several national strategies – including Vision 2030, the National Climate Change Strategy 2050, and the Integrated Sustainable Energy Strategy 2035 – as well as an investment plan. Together, these map out a pathway for energy transition and for pursuing sustainable economic development in an era of climate change. As part of this, the country set up a Green Financing Framework, which aims for half of public investment projects to be green by 2025 and launched, in 2020, the region’s first sovereign green bond, valued at $750 million. These strategies and frameworks demonstrate capacity and political ambition to address climate, enabling investors – climate funds and private capital – to identify opportunities and have confidence in the country’s desire to deliver on its climate, energy transition and sustainable economic development objectives. As a result, Egypt is the second largest recipient of foreign direct investments (FDI) in Africa after South Africa, according to UNCTAD's 2022 World Investment Report.8 This is despite financial and economic headwinds, such as high levels of debt and inflation, and rising unemployment.

Lengthy and Challenging Processes

The application process for accessing climate funding is intensive, lengthy, and requires significant levels of cooperation between multiple entities. For example, the GCF has established several National Designated Authorities (NDA) and country programmes to ensure that GCF-funded activities align with national priorities. However, application proposals for funding can only be submitted by GCF Accredited Entities (AEs), which are also responsible for channelling funding to recipient countries. AEs can be UN agencies, multilateral development banks, or international financial institutions. Regional and domestic bodies can also apply for accreditation; however, many are discouraged from doing so because the process is time-consuming and complex. Often, such entities do not have dedicated staff to work on the necessary documentation and to comply with the required standards.

Additionally, on project requirements, AEs are not always authorised to execute a project. Depending on project requirements, Executing Entities, such as multilateral institutions or NGOs, may be required to assume that responsibility.9

Moreover, the application process for, and documentation requirements of, funding proposals are rigorous, and financial and technical support may be needed just to complete one. For this purpose, AEs can tap into a sub-financing mechanism of the GCF, the Project Preparation Facility, to secure funding, which is capped at $1.5 million.

The climate funds have recently established more simplified application processes for small-scale projects, which require lower financial contributions. To access larger amounts typically takes years. In the case of the GCF and GEF, the processing of proposals takes on average four to five years from application to the implementation stage.10 This means that bottlenecks can occur at various points throughout the process. The implementation stage is also lengthy. The GCF database for programmes and projects for adaptation action shows that financing is disbursed throughout a project timeframe, between two and 12 years.11 The identified risks, the solutions to those risks, and sometimes the costs and currencies involved in a project, often change significantly between the time of application and the time of approval or implementation. Thereby, this reduces the efficacy and impact of the funding, as well as associated projects.

The Climate Catch-22

Countries with a proven track record in applying for, receiving, and implementing project financing from international climate funds have been shown to be more successful in accessing subsequent funding. This trend is mostly rooted in the enhanced capacity of these countries to develop investment plans, draft funding proposals, engage with the various agencies, and deliver on the expected key performance indicators.

Morocco and Jordan are cases in point. Morocco has been among the top MENA recipients of global climate finance: since 1997 it has received an estimated $1 billion in inflows for environment and climate projects. It is also a frontrunner in the region in putting in place a supportive regulatory environment. It has issued regulations and guidelines in support of voluntary climate finance reporting and ESG (environmental, social and governance) reporting in the financial sectors – banking, capital markets, and insurance – according to the Climate Finance Readiness Index 2023.12

Jordan, too, has a supportive governance framework and capacity for climate-related action, overall. Its efforts towards this end are supported by strong political will to make progress on its commitments. The country has incorporated climate into its national growth strategy, the Economic Modernisation Vision 2033, and was one of the first among Arab countries to publish its updated NDC following the 2015 Paris Agreement. Its NDC stipulated a financing requirement of $7.5 billion for mitigation measures with adaptation projects to be funded separately. Since joining the NDC Partnership in 2017, Jordan has prioritised turning its pipeline of climate-related projects into bankable proposals that can attract financing.13 In 2019 the government launched an NDC Action Plan, which, along with the Green Growth Action Plan, has been included in all ministry and national institution development plans to ensure a streamlined and integrated response to climate issues.14

The combination of political support and organisational capacity for climate-related activities in Jordan have made the country an attractive destination for development partners, investors, the private sector, and donors. It has attracted approximately $189 million in financing since 1996, ranking fourth in approved climate financing in MENA countries.

Elsewhere in the region, some countries are less able to access funding due to the need to establish and demonstrate a proven track record. Thus, some of the most at-risk countries are unable to make progress on adaptation and mitigation measures that are vital to human security, as well as to achieving net-zero targets. Drafting and approval of proposals requires a level of technical, and often financial, capacity that is out of reach for these countries (see section :Lengthy and Challenging Processes). Countries such as Iraq, Syria and Yemen are unable to demonstrate a history of experience because ongoing conflict and political instability have reduced both their interest in prioritising, and their capacity to address, climate issues. Additionally, global climate funds have little appetite to channel money to countries with high levels of risk – political, financial, social, and physical – and poorly equipped institutions able to receive, monitor, and disburse financing (see section: Highest Need but Highest Risk).

Clean Energy in the Spotlight

Energy-related projects receive the lion’s share of climate finance in MENA. The energy sector is the largest contributor to MENA’s greenhouse gas emissions, accounting for 38% of total sector emissions.15 Although the region’s emissions are low compared to other regions, several countries in MENA, particularly those of the GCC, are among those leading the world on emissions per capita.16 As energy consumption is expected to increase in the region, driven by economic and population growth and the impact of climate change, it is vital that countries reduce the energy sector’s carbon footprint.

On the global level, climate funds have prioritised low-carbon energy projects. In MENA, the CIF’s sub-fund the CTF, which focuses on clean energy technologies, is among the largest climate funders in the region. The GCF has also allocated 58% of approved funding for MENA to energy projects.

Consequently, countries that have prioritised renewable energy deployment, such as Morocco and Egypt, have attracted inflows. Morocco has enacted the required regulations to support the development of its renewables sector and has established a dedicated institution, MASEN, to oversee it. As a result, a total of 37% of its total installed generation capacity is from renewable sources and it has set a target of increasing this to 52% by 2030. Approximately 43% of Morocco’s total inflows from global climate funds is derived from one single renewable energy project, Noor, a concentrated solar power plant. The project was initially financed with $435 million from the CTF and leveraged $1.7 billion of financing overall. In general, the country has attracted significant FDI into, and regional attention for, its renewable energy industry. The Saudi Arabian-backed utility ACWA Power, which invests in and develops electricity and desalinated water projects, has the largest portfolio of renewable energy projects in Morocco.

Meanwhile, the largest share of Egypt’s FDI has flown into clean energy and technologies (CleanTech). The UAE has reportedly invested $25 billion in developing Egypt’s CleanTech sector.17

Highest Need but Highest Risk – Conflict-affected Countries Lose Out

MENA countries with some of the highest needs in terms of combatting the impacts of climate change are currently receiving among the lowest amounts of environment and climate finance. Fragile, or conflict-affected states, such as Iraq, Yemen and Syria, find it difficult to meet the eligibility criteria for international financing from climate funds. This is in large part due to their inability to establish adequate institutions and regulations due to ongoing conflict or political instability.

For countries experiencing ongoing conflict, the issue of climate is often pushed down the agenda, resulting in low prioritisation of climate action and funding – both nationally and within the framework of international multilateral arrangements. Governance capability is also negatively affected, resulting in little to no institutional capacity to consider and act on climate issues.

Conflict environments also hinder the collection of climate-related data, either due to lack of personnel, damage to facilities or inadequate resources to dedicate to the task. This means that it is difficult to report on climate and emissions and to forecast and therefore prepare for upcoming weather events. This situation makes this group of countries even more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change and less ready to adapt to or mitigate against them.

At a basic level, conflict countries have been slower in engaging with the UNFCCC and its related processes, meaning that they do not have in place many of the different UNFCCC-mandated climate documents which are used as reference points for climate finance. For example, neither Syria nor Yemen have developed national adaptation plans and neither Iraq nor Syria have submitted biennial update reports to the UNFCCC.18 Yemen’s NDC dates to 2015 and was submitted as an intended contribution; it has not been updated since. Similarly, Syria’s national communication to the UNFCC was submitted in 2010 and has not been revised since. Additionally, Syria officially joined the 2015 Paris Agreement at the end of 2017.

Deteriorating or unsafe security environments, as well as political instability, also act as deterrents to

climate funds. These conditions have already caused delays to, or the cancellation of, approved projects in

these three countries, adding to funds’ hesitance to allocate them additional climate finance. For example,

a

GEF-funded project to accelerate the exploration and development of geothermal power use in Yemen was

cancelled

due to insecurity issues related to the Arab Spring, lack of co-financing from partners due to perceived

risk,

and staff disbandment after the start of the civil war.19

Similarly, another GEF project – this time in Syria – that aimed to reduce GHG emissions from buildings by

implementing thermal and energy efficient building codes for new construction was suspended and later

cancelled

due to unsafe travel conditions across the country. Buildings selected by the project had also been damaged

or

destroyed because of the conflict.20

There is also insufficient international climate finance dedicated to local action, despite the importance of empowering communities to address climate challenges having been highlighted and demonstrated through projects run by independent non-profits, such as the 15th Garden project in Syria. This lack of specific localised funding impacts the ability of communities to make progress on or prepare for climate-related issues in the absence of national-level focus and capacity.

Conclusion

The MENA region faces some of the most severe impacts of climate change, yet its ability to attract much-needed climate finance is not determined by levels of vulnerability and need, but instead by each country’s institutional capacity, experience in engaging with the UNFCCC and co-financing processes, and the application and approvals systems of international climate funds.

This has led to marked inequality between climate funding recipients within the region. Countries that have laid out national strategies, including investment plans, to combat climate change are more likely to attract climate financing and co-financing, and as a result, can build a track record with global climate funding institutions. This stands them in good stead for accessing further financing, specifically for clean energy and clean technology-related initiatives.

However, least developed countries and those affected by conflict and political instability continue to struggle, not just with the immediate impacts of climate change and the threat of increasing temperatures in future, but to meet global climate funds’ criteria. This severely limits their ability to access climate financing, leaving them not only underfunded, but underprepared. The impact of climate change on the MENA region will be great – as will the impact of low levels of financing to combat it.

Appendix: Granular Analysis of Green Funds

For the purposes of this report, an in-depth analysis was carried out of the three largest climate funds, including their sub-funds, that MENA countries can access. In total there are 24 climate funds that cover the region. The study revealed differences across the funds in terms of debt-to-grant ratios, co-financing requirements and levels, targeted projects and countries, and other characteristics. The findings are described in detail in this section.

1. Overview

The Climate Investment Funds (CIF) operates ten multi-donor trust programmes. Of these, three are active in the MENA region. The largest is the Clean Technology Fund (CTF), which has disbursed 99.58% of CIF investments in the region. The CIF was established in 2008 to deliver climate finance for pilot projects in climate solutions and for scaling-up such projects in low- and middle-income countries.21

The Green Climate Fund (GCF) was established under the Cancún Agreements in 2010 as a financing mechanism of the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement, with a mandate to support developing countries to achieve their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). Its first project was approved in 2015.

The Global Environment Facility (GEF) operates several funds, which target biodiversity loss, climate change, pollution, and strains on land and ocean in developing countries.22 They provide grants, blended financing, and policy support for both the private and public sector, and civil society organisations. Three of the funds are the Special Climate Change Fund (SCCF), the Least Developed Countries Fund (LDCF), and the Adaptation Fund. The latter covers the Adaptation for Smallholder Agriculture Programme (ASAP) as well. The LDCF covers Yemen, Djibouti, and Sudan within the MENA region.

Of the 24 funds that cover MENA, three are only accessible to North African countries. These funds are the Canada-African Development Bank Climate Fund (CACF), the African Adaptation Benefit Fund (ABM/AABF), and the African Risk Capacity (ARC). Additionally, some funds cover only one or two countries in MENA, such as the Danish Climate Investment Fund (KIF), which has only been active in Egypt thus far.

2. Green Climate Fund

The GCF is the world’s largest climate fund and MENA’s largest climate funding contributor.23 Yet, the cumulative GCF financing of MENA countries constitutes less than 8% of the fund’s total approved financing of $12.7 billion, as of November 2023.

Out of a global total of 119 projects approved in 148 developing countries that are receiving GCF funding, 24 include MENA countries. Eight countries from the region participate in these. The cumulative total financing of these 24 projects, which may involve multiple participating countries including countries outside MENA, amounts to $2.5 billion, or 20% of the fund’s approved financing; some 68% of the $2.5 billion takes the form of loans. MENA’s share of the $2.5 billion stands at $967 million.

The eight countries in the MENA region with approved GCF project financing are Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, Tunisia, Lebanon, Sudan, Bahrain and Djibouti. Approximately 62% of the projects are multi-country/global projects that span MENA, Africa, and beneficiaries in the “Least Developed Countries” (LDCs) category, or small island developing states. Single-country projects are recorded in only five MENA countries: Egypt, Bahrain, Morocco, Jordan and Sudan. In addition to project financing, the GCF has financed several readiness programmes in five MENA countries: Algeria, Iraq, Yemen, Syria and Oman. Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait have established GCF country offices without any listed projects.

The $967 million GCF fund in MENA could see a mobilisation of approximately $3 billion in co-financing. However, 68% of the GCF financing for MENA is in the form of loans; only 32% of the funding is grants.

Part of the GCF’s mandate is to mobilise private sector financing for climate projects. Data on the projects that include MENA countries show that the fund mostly targets the private sector, providing it with 81% of climate funding, while the public sector is a beneficiary of the remaining 19%. Additionally, 36% of GCF funding targets climate mitigation measures; 54% cross-cutting projects, which are projects that have both adaptation and mitigation aspects; and 10% goes towards climate adaptation measures, despite the region’s significant need for adaptation to the impact of climate change.

In terms of sectoral areas, energy projects receive the largest share of GCF funding targeting MENA countries, equivalent to 58%. Meanwhile, water projects receive 8%, and agriculture projects 6%. The remaining 28% of funding targets all other areas covered by the GCF.

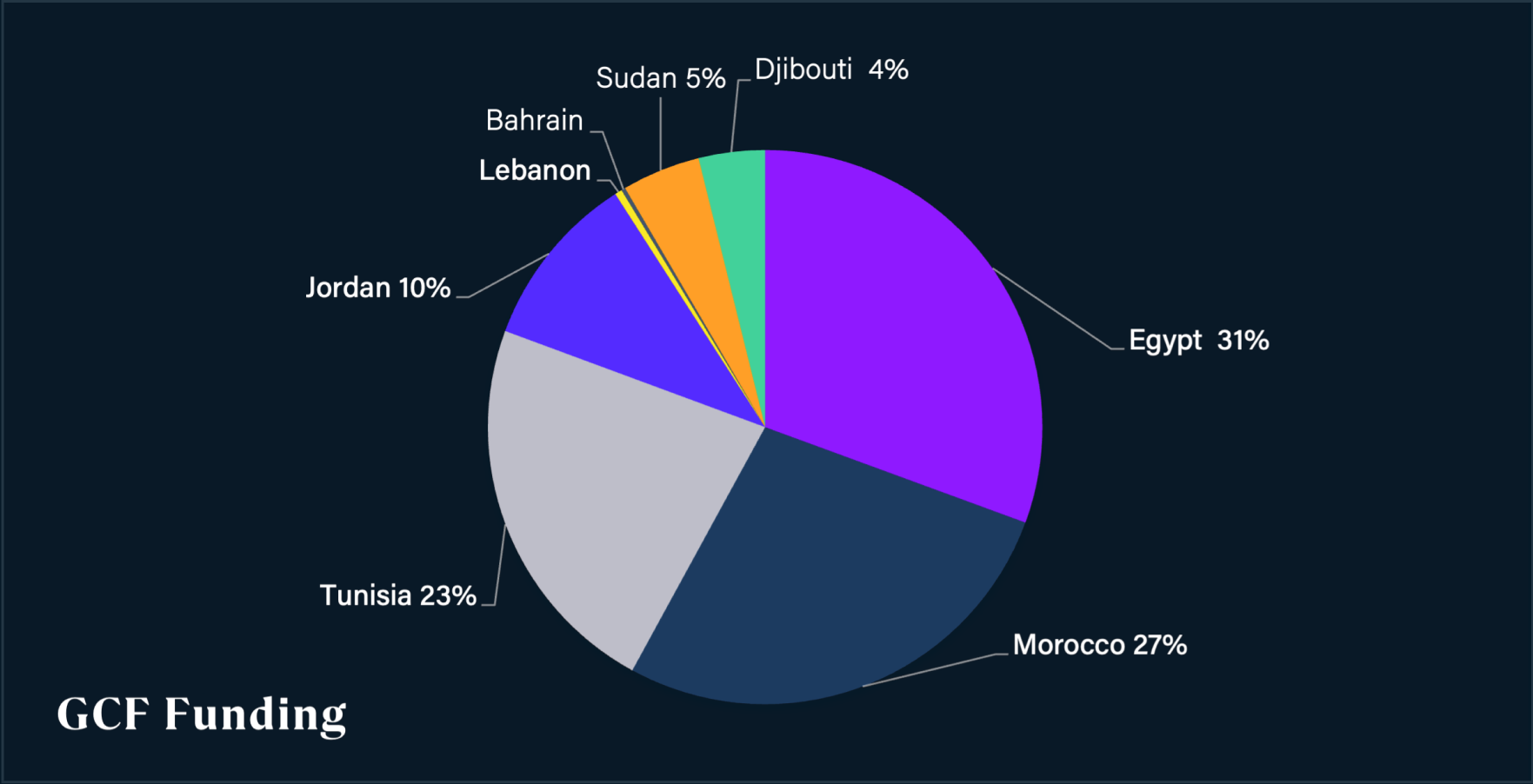

The GCF typically seeks projects covering eight mitigation and adaptation areas: 1) health, food, and water security, 2) livelihoods of people and communities, 3) energy generation and access, 4) transport, 5) infrastructure and built environment, 6) ecosystems, 7) building, cities, industries, and appliances, and 8) forests and land use. These areas serve as reference points to guide stakeholders in developing projects. Figure 5 shows the GCF funding share per country in the MENA region.

Egypt holds the largest share of GCF financing in MENA, at 31%, followed by Morocco (27%). Egypt also holds the largest debt to grant ratio: some 85% of its financing is in the form of loans. This compares to 55% in Morocco.

Tunisia accounts for 23% of the GCF’s MENA financing with loans constituting 79% of the financial support. Jordan’s share is 10%, of which 56% is in the form of loans. Sudan and Djibouti’s shares in total financing are each less than 5%; approximately 14% and 12% of financing approved for these countries is loans, respectively. All five projects in Djibouti are part of global projects, whereas two of the three projects in Sudan are single-country projects. The lowest shares of total financing are held by Lebanon and Bahrain; the cumulative total allotted to these countries is less than 1%, but it is all in grants.

The key implementing partners of GCF-funded projects in MENA – meaning those involved in more than one project with participants from the region – are Agence Française de Développement and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD).

3. Global Environment Facility

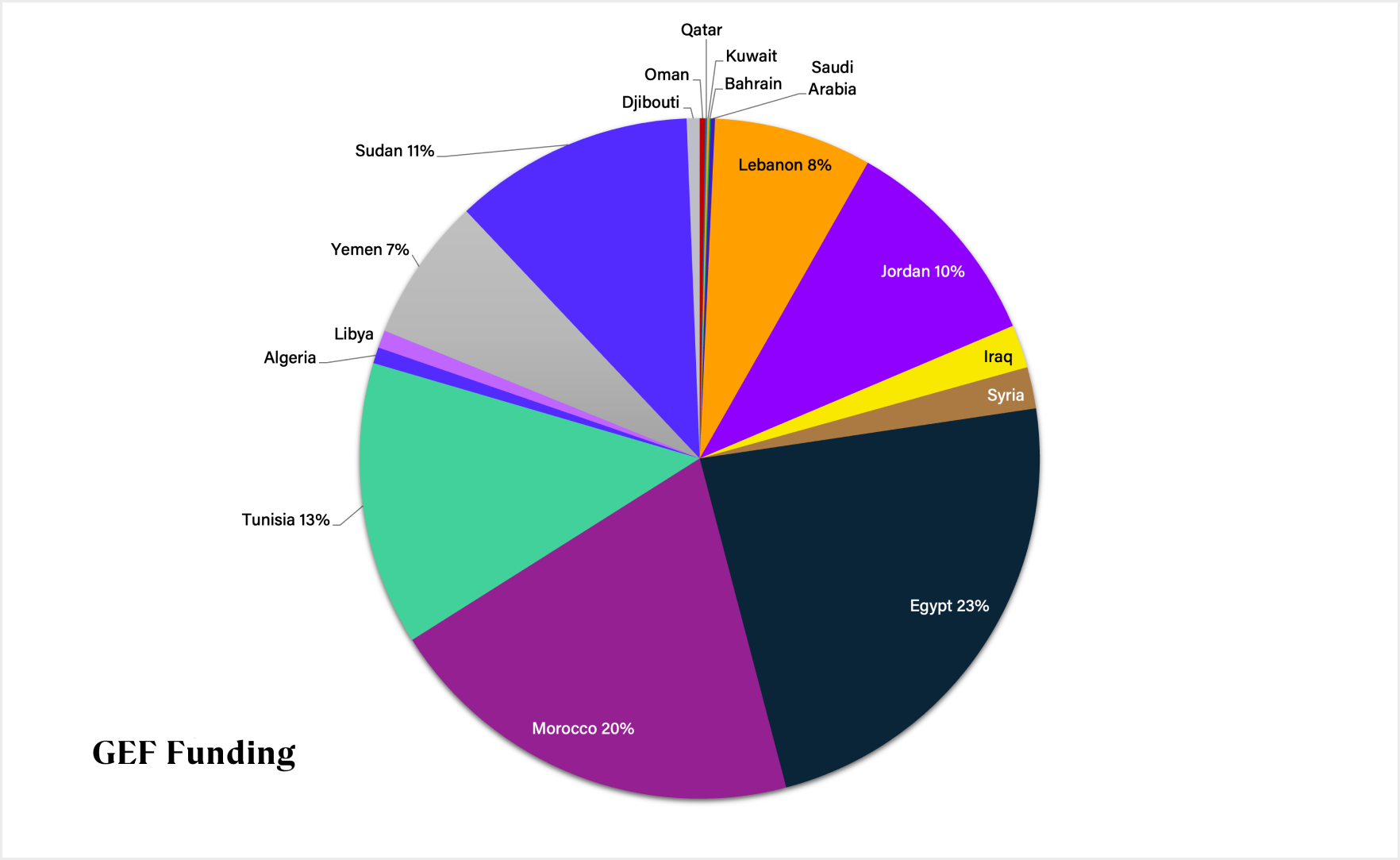

Between 1992 and 2023, and through eight replenishment cycles (GEF-1 to GEF-8), the GEF has approved financing of more than $1 billion for 315 national, regional or global projects that include one or more MENA countries. The fund has mobilised more than $6.7 billion in co-financing. Whereas data on the financing per MENA country is not available, an adjustment of projects’ value to include only MENA countries results in an estimated $858 million in GEF financing. This share constitutes less than 4% of the GEF’s total financing, which has made $23 billion available to 5,000 single- and multi-country projects across the world in the past three decades, exclusive of co-financing amounts.

The 315 projects have covered 17 MENA countries, or all MENA countries considered for this study except the UAE and Palestine. However, projects vary widely in terms of numbers and sizes across the various countries in the region. A total of 24% of these projects are regional or global, including up to 62 countries per project.

Globally, the highest share of GEF funding is granted to biodiversity projects. In MENA, 36% of the approved projects are attributed to biodiversity, or cross-cutting projects covering biodiversity, climate change, and/or land degradation.

The GEF implementing agencies are mostly the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the United Nations Industrial Development Organisation (UNIDO), the International Fund for Agricultural Development, the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), the World Bank, and the EBRD. Figure 6 shows the GEF MENA funding breakdown per country through eight replenishment cycles.

The GCC countries’ (minus the UAE) share of GEF financing amounts to $6.2 million covering 19 projects. These are mostly multi-country programmes for the preparation of climate and biodiversity-related reports and communications, particularly for the UNFCCC. Most of the projects were implemented by the UNDP and UNEP. National projects constitute 37% of the total funding for GCC countries, another 37% comes through global projects of which GCC countries are part, and the remaining share is for regional projects.

The Levant’s share (Jordan, Lebanon, Syria and Iraq) of GEF finance exceeds $188 million for 141 projects, with almost $1 billion in co-financing. Palestine has received no financing from the GEF and Syria’s last GEF project was implemented in 2013, during the GEF’s fifth replenishment cycle, GEF-5. National projects constitute 51% of the Levant’s projects funded by GEF.

North Africa (Egypt, Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria, and Libya) has attracted the largest amount of GEF financing in MENA for the largest number of projects, with a cumulative total of $502 million – more than double the Levant’s funding, and 81 times that of the GCC. A total of 74% of North Africa’s funding is for projects in Egypt and Morocco. Meanwhile, Algeria and Libya have almost 1% of North Africa’s share each. The GEF funding covered 220 projects and mobilised more than $4.2 billion in co-financing. Some 51% of the projects are either regional or global projects. Almost half of the projects funded by GEF in North Africa are national projects. Egypt and Morocco’s share of national projects exceeds 57% of the two countries’ projects, whereas Algeria and Libya have no national projects. Least Developed Countries

LDCs (Sudan, Djibouti and Yemen) have accrued lower levels of GEF funding than North African and Levant countries. Collectively, they have been allotted $160 million for 78 projects, 68% of which are national projects. Yet, funding allocations between LDCs have wide discrepancies as Sudan’s GEF financing is 18 times Djibouti’s funding. In fact, Djibouti has the lowest share of financing compared to countries in North Africa and Levant, and the country has not received any GEF financing since 2017.

4. Climate Investment Funds

MENA’s share of CIF total financing stands at 16%, equivalent to $860.7 million, covering 16 projects, and it has mobilised $12.65 billion in co-financing.

Clean Technology Fund

The CTF is the largest CIF investment provider in the MENA region. The CTF enables clean energy transition

in

developing countries and was established to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from the energy sector, as

the

largest source of emissions globally.

CTF funding in the MENA region stands at $857.16 million, representing 99.58% of CIF’s MENA funding. The bulk of this financing is in loans. Globally, the CTF has financed 161 projects in 34 countries, valued at $5.3 billion, with an additional $55.8 billion in co-financing. The bulk of the co-finance comes from the private sector ($18.1bn) and multilateral development banks ($16.2bn). Of these 34 countries, only six are in the MENA region: Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria, and Libya. The latter two countries have so far only prepared CTF investment plans with no approved project on record as per CIF’s website.24 Asia heads the list of the CIF’s recipient regions with 32% of the fund’s financing, followed by Europe and Central Asia with 17%.

The key implementing partners for MENA projects are the African Development Bank, Asian Development Bank, the EBRD, Inter-American Development Banks, and the World Bank Group.

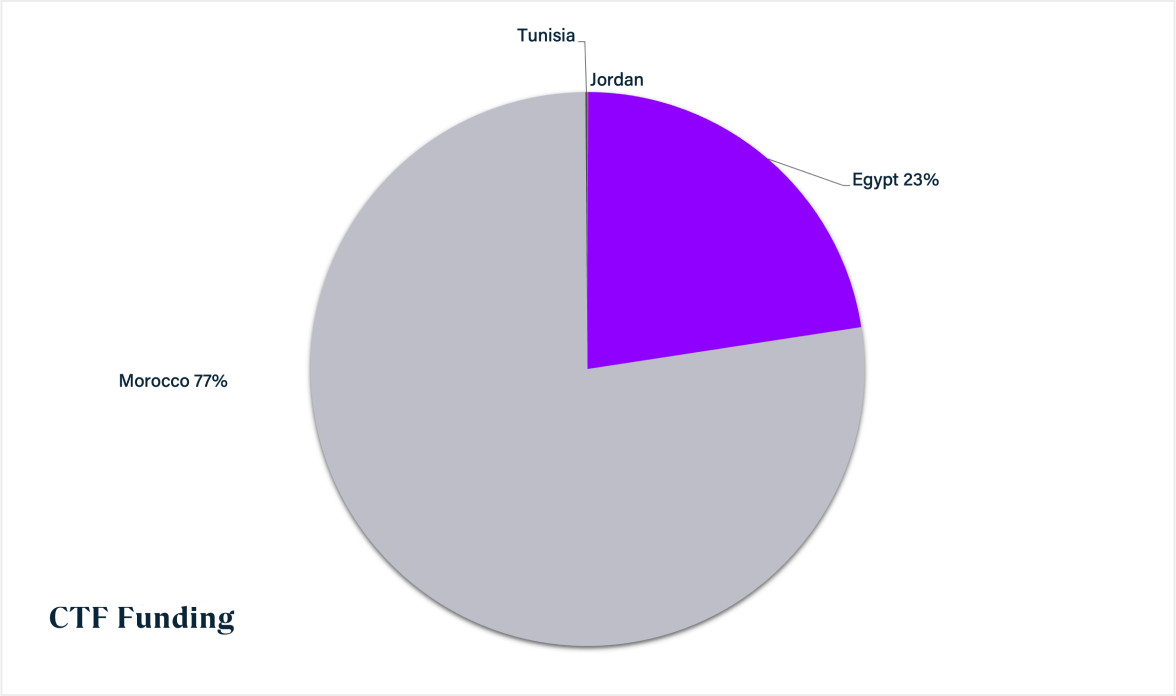

As portrayed in Figure 7, Morocco holds the largest share of CTF funding in MENA at almost 77%, whereas the share of both Tunisia and Jordan is less than 1%.

All CTF projects fall within the category of climate mitigation efforts. Tapping into the CTF requires the recipient country to develop an investment plan that fits its national priorities and lays out mitigation measures. The fund helps in mobilising co-financing streams to scale up clean energy projects.

CTF-funded projects in MENA all fall within two categories within climate mitigation: renewable energy and energy efficiency. Globally, the CTF covers four types of projects, with a primary focus on renewable energy projects (64% of its financing has been directed towards projects in this space), another 14% for energy efficiency, 6% for transport, and finally the smallest share, 2%, towards the deployment of energy storage systems. CTF has four key indicators: 1) annual GHG reductions, 2) annual energy savings, 3) cumulative co-financing, and 4) cumulative installed capacity.

Footnotes

- 1 Ezzeldin, Khaled, Daniel Adshead, and Paul Smith. 2023. Adapting to a New Climate in the MENA Region. UN Environment Programme Finance Initiative. https://www.unepfi.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Adapting-to-a-new- climate-MENA.pdf.

- 2 United Nations. Introduction to Climate Finance. UNFCCC. Accessed November 2023. https://unfccc.int/topics/introduction-to- climate-finance#:~:text=Climate%20finance%20refers%20to%20local,that%20will%20address%20climate%20change.

- 3 NDC Partnership. Climate Funds Explorer. ndcpartnership.org. Accessed November 2023. https://ndcpartnership.org/knowledge- portal/climate-funds-explorer.

- 4 United Nations ESCWA. 2022. Review of Policy Brief: Climate Finance Flows in the Middle East. UNESCWA. https://www.unescwa.org/sites/default/files/pubs/pdf/climate-finance-needs-flows-arab-region-english.pdf.

- 5 Think - SRMG. September 2023. MENA Forum Report: The Case for Cooperation beyond De-Escalation. SRMG Think Research and Advisory. https://srmgthink.com/en/featured-insights/annual-report/19/mena-forum-report-the-case-for-co-operation-beyond-deescalation.

- 6 The Green Climate Fund. The Five GCF Modalities. Green Climate Fund. Accessed November 2023. https://www.caribbeanclimate.bz/gcf/about-gcf/five-gcf- modalities/#:~:text=Funding%20Proposals%20submitted%20to%20the,social%2C%20gender%2C%20and%20legal.

- 7 UNDP-GEF. How to Apply for GEF Funding. www.un.org. UNDP-GEF. Accessed November 2023. https://www.un.org/esa/sustdev/csd/csd14/lc/summary/gef.pdf.

- 8 UN Conference on Trade and Development. 2022. World Investment Report 2022. UNCTAD. https://unctad.org/system/files/official- document/wir2022_en.pdf.

- 9 Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation. 2021. How to Access the Green Climate Fund. SDC Climate Change and Environment Network. https://www.shareweb.ch/site/Climate-Change-and- Environment/Documents/How%20to%20access%20the%20Green%20Climate%20Fund-2021.pdf.

- 10 Global Environment Facility. 2004. Review of Biodiversity Program Study 2004. GEF Council. https://www.gefieo.org/sites/default/files/documents/council-documents/c-24-me-inf-01.pdf.

- 11 Green Climate Fund. Project Portfolio. GCF. Accessed November 2023. https://www.greenclimate.fund/projects.

- 12 J.A. Tahiri, M.W. Aaminou, 2023. Climate Finance Readiness Index Report 2023. Green For South Inc, Toronto, Canada. https://gaif.org/Archive/ce5cd875.pdf.

- 13 The NDC Partnership is a voluntary, free-to-join organisation established at COP 22 in Marrakech in 2016, following the Paris Agreement in 2015. It was set up to enable a more coordinated approach to achieving NDC targets. The Partnership aims to facilitate access for developing countries to support - technical assistance, finance, and expertise – and to provide a mechanism for greater collaboration between country governments, international institutions, non-state actors and other partners. Not all MENA countries are members.

- 14 NDC Partnership. Jordan country page. NDC Partnership website. Accessed November 2023. https://pia.ndcpartnership.org/country-stories/jordan/.

- 15 Sebastian Timmerberg, Anas Sanna, Martin Kaltschmitt, and Matthias Finkbeiner. 2019. Review of Renewable Electricity Targets in Selected MENA Countries – Assessment of Available Resources, Generation Costs and GHG Emissions. Energy Reports 5 (November): 1470–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2019.10.003.

- 16 The World Bank Group. Middle East and North Africa Climate Roadmap (2021-2025). The World Bank. https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/6f868d4a875db3ef23ef1dc747fcf2ca-0280012022/original/MENA-Roadmap-Final-01-20.pdf.

- 17 EY. 2023. EY Africa Attractiveness Report 2023: South Africa, Egypt at Forefront of FDI Projects. EY Press Release. November 15, 2023. https://www.ey.com/en_za/consulting/ey-africa-attractiveness-report-2023--south-africa--egypt-at-for.

- 18 International Committee of the Red Cross and Norwegian Red Cross. 2023. Making adaptation work – Addressing the compounding impacts of climate change, environmental degradation and conflict in the Near and Middle East.

- 19 Independent Evaluation Office, GEF. 2020. Evaluation of GEF Engagement in Fragile and Conflict-Affected Situations. https://www.gefieo.org/sites/default/files/documents/fragility-2020-approach- paper.pdf#:~:text=Despite%20the%20GEF%E2%80%99s%20substantial%20investment%20in%20programming%20in,are% 20not%20adequately%20taken%20into%20account%20or%20mitigated.

- 20 Independent Evaluation Office, GEF. 2020. Evaluation of GEF Engagement in Fragile and Conflict-Affected Situations.

- 21 Climate Investment Funds. 2023. Middle East & North Africa. CIF. https://www.cif.org/country/middle-east-north-africa.

- 22 Global Environment Facility. GEF homepage. Accessed November 2023. https://www.thegef.org/.

- 23 Green Climate Fund. GCF homepage. Accessed November 2023. https://www.greenclimate.fund/.

- 24 Climate Investment Funds. Algeria. CIF.org. Accessed November 2023. https://www.cif.org/country/algeria; and Climate Investment Funds. Investing in Libya. CIF.org. Accessed November 2023. https://www.cif.org/country/libya#:~:text=Libya%20is%20also%20among%20the,lack%20of%20capacity%20and%20knowledge.